This year, the Japanese role-playing game Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne celebrates its twentieth anniversary. The apocalyptic world of Nocturne revolves on the struggle of its many inhabitants, and yet, the game’s players can’t help but feel isolated among the ruins.

(For a quick intro to SMT3, and to read the rest of the series, click here.)

The way the game alienates its audience is unique to each player, but the game uses four primary methods to achieve this sense of alienation: disorienting environments, inconsistencies in time, imbalanced relationships, and estrangement from humanity.

This is an informal essay about how a video game makes people feel. Subjectivity is unavoidable, but the purpose can be considered more objectively. Why does this game go to such efforts to unsettle its players? Alienation for its own sake is enough. Frisson between the compelling unfamiliar and the uncomfortable, in a deliberate and artistic setting, is thought-provoking, can even be fun. But much like the Conception, the sense of alienation serves the development of a Reason.

ENVIRONMENT

The success of any work of fantasy relies on its ability to make the strange familiar, and the familiar strange. This process is uses ‘recalibration scenes’, the storytelling equivalent of the light level adjustment prompt at the beginning of some video games. These scenes are where familiar elements are first shown to work in tandem with those created for the story—people, flora and fauna, politics, philosophy, physics, etc.

After this juxtaposition, fantasy can do its dual work—escapism and commentary on reality. Without the everyday, there is little satisfaction in having left, and without the strange, there is no seeing what compares with what’s back home.

Recalibration scenes are fairly straightforward for a majority of twenty-first century apocalyptic settings. The new, living amid the bones of the old, makes for handy dissonance. Sometimes a work only needs one; sometimes it needs several to not overwhelm the audience (though ideally, each recalibration scene is at least a little whelming, or it’s no fun).

What keeps this older game a unique vision among all the varieties of recreational apocalypse available is that it recalibrates in a specific way. The Vortex World undergoes multiple cycles of civilization and ruin, and each group’s rise and fall is an argument about a possible new world. In apocalyptic settings, architecture is a handy tool for recalibration, thanks to destruction and decay. Three different categories of architecture exist in the Vortex World. Places that were built by humans in the previous world, places that seemingly came into being by the will of Kagutsuchi at the beginning of the Conception, and places that have been built by the inhabitants of the Vortex World.

The areas constructed by humans are treated differently depending on their new occupants: preserved, emptied, smashed up, reassembled. Inhuman environments are varied, but generally fit an ancient/far-future ambiguity appropriate to the apocalyptic and gestational end-is-the-beginning symbolism of the Vortex World.

These places are distinguished with geometric, modern or traditional Japanese elements associated with the faction in control. These simple and powerful designs are rendered in bristling highlights and shadows. They extrapolate upon a few elements, which appear in as many ways as possible. This follows with the point of the Vortex World, which is to establish a single ideology that will determine the new world’s future.

These inhuman spaces are not uninhabitable—they’re just not for you.

Built by humans and destroyed (indirectly) by humans, the ruins of Tokyo are where the Demi-fiend once lived, maybe got a part-time job, studied, goofed off. There are ruins, too, of the places where he was excluded, due to age or status. These relationships to place defined his own place in human society.

In the Vortex World, not only are these relationships upended, but the buildings’ new purposes ask him all over again: Where do you belong?

Ikebukuro isn’t just a complex made eerier by the broken glass and piled-up junk. It’s the stronghold of Mantra demons, and they’ve transformed an old skyscraper from the inside out (or built new) to better suit their bloody tastes. To be able to exist in Ikebukuro, the Demi-fiend must win a sham trial by combat, instead of buying something or having business there.

Composer Shoji Meguro’s music combines meditative ambience, driving strings, and retro-reinterpreted earworm jazz, rock, and electronica. This surreal soundtrack provides crucial insight into the precarious stability of the Vortex World. The malls of Shibuya and Ginza might be haunted by demons, but since those places are where demons go about their daily business, the music is upbeat. Asakusa’s precarity and broken cultural continuity is felt in its droning tones.

Because conflict keeps changing the Vortex World, these places keep changing, too, and what’s considered unusual keeps changing. What relationship does the Demi-fiend have, or want, with these new spaces? How can he consistently define himself and keep true to others when the world insists on strangeness?

INCONSISTENCIES IN TIME

Clotho, the spinner of the thread of fate, tells the Demi-fiend, “Kagutsuchi repeats the process of birth and death. It will not wait for you.”

While this is a very specific hint to a very specific puzzle, it captures the Demi-fiend’s relationship to the world around him. The Demi-fiend is always moving from place to place, and few areas stay the same while he is gone. The result is that he is always considered a visitor.

One second, the Demi-fiend is at the epicenter of news that shakes the world; the next, he’s the last person to know what’s going on. He’s out of the loop from the start. By the time the Demi-fiend wakes up from his demon worm implant,

—Macca has replaced the yen, and new stores have been standardized in signage recognizable across the cities

—the Fairies have splintered, and those who have soured on the Vortex World have sealed themselves in Yoyogi Park while others have joined Nihilo or Mantra

—Hikawa has gathered together the Assembly of Nihilo and begun planning the Nightmare System

—the demon Gozu-Tennoh has established the Mantra and enslaved the Manikins, has likely constructed the new skyscraper and Kabukicho Prison, which could only happen after

—Manikins formed at Mifunashiro and left the area entirely. For all the place’s available Magatushi, it’s become a region of so little strategic significance that Nihilo doesn’t bother surveilling its Amala terminals

—demons and souls have accessed the Amala Network, resulting in friction between those entering it to seek Magatsuhi and those seeking solitude

—the inhabitants of the Vortex World have largely forgotten about the Amala Temple.

The events of the Vortex World take place in a state where the mythic and the moment are interchangeable, in which the steps toward creation are taken in an eternity and an instant. The Vortex World still exists within the flow of time. Everything that happens in the Vortex World is a consequence of someone’s choice, and events happen in order. What doesn’t add up is the passage of time between those events. If the flow of time is taken too literally, then Manikins hang their laundry in practically the same geological span of time needed for the new rivers to sculpt their holy land from the rock.

So yes, it’s completely insane that Chiaki and Isamu apparently travel on foot without demon companions and get to places faster than the Demi-fiend. The player’s experience of his journey exaggerates these discrepancies to show how time passes differently for any two people.

It’s one thing to realize that you don’t experience things the same way as anyone else. It’s another to really comprehend that others experience things differently than you do. If the player can only understand a fraction of what the Demi-fiend is experiencing, imagine the gulf between the player and the inhabitants of the Vortex World.

IMBALANCED RELATIONSHIPS

The occult journalist Hijiri is the only human (fine, assumed human) the Demi-fiend regularly interacts with. He observes that the Vortex World is a place where “one life doesn’t amount to much, and human relationships are pretty much nonexistent.”

The Vortex World is not a lonely place. No matter where he is, the Demi-fiend is about ten seconds away from interaction with another person. Most of the time, that person is a demon who wants to kill him.

The reason could be anything: hunger for Magatsuhi, boredom, the defense of an area critical to an ideological faction. The breakdown of these factions makes random demon encounters feel less random. A party of roving demons known to be associated with the Assembly of Nihilo isn’t so obviously the output of game code; it’s the result of Hikawa organizing a patrol. Demons in the Labyrinth of Amala aren’t mindless experience fodder; they’re gathering around Lucifer.

This agency is strongest when the Demi-fiend attempts to negotiate with them for their allegiance. While the Demi-fiend is strong in his own right, he guarantees his safety as he crosses the Vortex World by getting demons to join him.

Demon negotiations are littered with mythology in-jokes, incoherent moans and death threats, accusations of being a cheapskate, and the rare piece of advice. Negotiations sometimes end with the demon asking the Demi-fiend a philosophical question; the discourse of creation touches all residents of the Vortex World.

Negotiation is about a demon’s survival. It usually only works after the Demi-fiend has killed or run off a demon’s friends. Alone, that demon bargains their allegiance for as much Macca and items as they can squeeze out of the Demi-fiend, or else stalls until they can slip away. Sometimes they need convincing—or threatening, or assurance—from one of the Demi-fiend’s demon allies.

Even if they accompany the Demi-fiend based on philosophical compatibility, this is a more direct choice about survival than being choosy about one’s friends in the previous world. The Vortex World is about to be shaped by some ideology or other, and it’s not guaranteed that demons will even have a place in the world to come. The battle to shape the new world is a contest of strength. By going along with someone strong that they agree with, they’re more likely to come out of it alive.

Negotiation is the most readily available form of interaction in the Vortex World, but for all its variety, it’s not so much a genuine exchange as it is a transaction. A conversation with the occasional wandering soul sometimes isn’t enough to counteract the feeling that people only engage with the Demi-fiend to get something out of him, whether it’s his ideological support, his protection, or his Magatsuhi—his life.

This isn’t to say that the Demi-fiend’s demon followers aren’t his companions. They sometimes talk to the Demi-fiend after battle. These interactions feel unique enough, since demons are grouped into a large range of personality types. As a result, demons offer him items out of pity or a crush as often as a sense of hierarchy.

The Vortex World may be the blighted remains of Tokyo, but because the Demi-fiend is never really alone, it still feels like an urban area. Isamu articulates that urban paradox of isolation surrounded when he shares his ideology. Moment after moment of encountering strange lives, sometimes with little time or context to grasp them and understand the choices they make, which accumulate into determining the course of your own day. When you manage to make a connection in that busy urban environment with someone with a different life from yours, you learn something new about what it means to live a human life.

One of the first demons that the Demi-fiend talks with is a Shiisaa who takes one look at his tattoos and gives him some supplies, commiserating that demons have it rough. This introduces a necessary weirding shift in perspective from the obvious plight of the once-human souls in danger of being devoured by demons, to the plight of those hungry demons. In the Vortex World, having that brief relatable exchange with a soul or a demon doesn’t necessarily reinforce the Demi-fiend’s connection to humanity.

Emotionally and mentally, the Demi-fiend is on his own. With the brief exception of Pixie, his demon allies don’t engage with him or anyone else outside of battle and have nothing to say about the conflicts of the Vortex World. Even if they were recruited away from Nihilo or Yosuga, that change of heart is the last word on what they think about what’s going on. With the ideological pressures the Demi-fiend’s human friends are putting on him—for the sake of the world’s future, no less—support outside of battle might be welcome.

ESTRANGEMENT FROM HUMANITY

From the moment that Lucifer singles out the Demi-fiend, his humanity is in flux. Just like the Vortex World, born from the ruins of the old, an undetermined future. Most strangers take one look at the Demi-fiend and assume he’s a demon. This makes sense, since there are many more human-shaped demons around than actual humans. Most of the humans the Demi-fiend knew, though, eventually come to the same conclusion.

After the Conception, occult writer Hijiri recognizes him as the kid he chatted with at Yoyogi Park. Since Hijiri’s still in the process of accepting that demons are real, he doesn’t consider the Demi-fiend one of “them”. By the time the two are experimenting with travel through the Amala Network, though, Hijiri’s already joking “guess you didn’t become a demon for nothing.”

Chiaki’s first impression of her friend’s new look is buried under ten layers of emotional fatigue, but Isamu takes one look at immediately thinks demon. After, Isamu talks freely about relying on the Demi-fiend’s demonic power to brute-force through obstacles, just as Hijiri does.

A couple of people look at him and seem to consider him the person he was, though it’s uncertain whether they’re accepting his new demonic body or setting it aside. One is the soul of a fellow student, who recognizes him through the tattoos. Another is his teacher, who never calls him Demi-fiend or remarks on the change, even though she’s familiar with the Demi-fiend as a figure in the Scripture of Miroku (possibly because he wouldn’t have become the prophesied Demi-fiend if she hadn’t saved him).

His relative humanity in the eyes of the others who are trying to conceive a Reason, though, seems to mostly be contingent on his support.

If the Demi-fiend rejects Chiaki’s ideology, she never criticizes the Demi-fiend for his demonic traits, considering she too has taken in considerable demonic power. Instead, she is bewildered that he doesn’t use his power the way she thinks a demon should. She declares their friendship ended, rejecting their shared human past. Isamu snidely implies that the Demi-fiend gave up his humanity willingly if he doesn’t encourage Isamu’s Reason, Musubi. Hikawa seems to only care about the Demi-fiend’s nature because it’s relevant to his plans, but is quick to dismiss him as a “mere demon” too consumed with greed to see the merits of Shijima (it would be fascinating to hear Hikawa talk to his supporters about their demonic natures).

The Manikin prophet Futomimi first thinks the Demi-fiend is a human, despite his appearance. During the massacre Chiaki leads against the Manikins at Mifunashiro, he pleads for the Demi-fiend’s help, believing the Demi-fiend has “a heart unlike that of any demon”.

If the Demi-fiend instead kills him for Chiaki, then he curses the Demi-fiend as a foul demon before he dies—though the Demi-fiend’s participation in the massacre is a bit more of an immediately relevant rejection than telling Isamu or Hikawa their ideas are lame.

Under this judgment is the assumption that demons are incapable of restraining their greed, or of understanding some bigger goal. Hearing from everyone that he’s something weird but definitely not human, being outright called a demon, can sure start to solidify any questions the Demi-fiend might have about his true nature, even as he tries to decide where he stands.

Those associated with Lucifer also take it upon themselves to voice their opinions on whether the Demi-fiend is more human or demon. This, however, is more of a measure of worth and a recruitment tactic, since Lucifer’s secret goal is for the Demi-fiend to abandon his humanity to become a demon of chaos to wage war against the Great Will.

THE UNCANNY INHUMAN: SOULS AND MANIKINS

When the Demi-fiend first wakes to a devastated Tokyo, his clearest directive amid the chaos is to find his teacher, who has promised to explain why the world came to an end, and what better world will take its place.

Beginning this search, he runs into the ghostlike souls of the deceased humans, who think he’s one of the countless demons that have overtaken Tokyo. The city’s new occupants live simultaneously incomprehensible and familiar lives, devouring each other or sharing a nightclub, depending on their individual personalities and politics.

Most of the Vortex World’s inhabitants are demons, but humans are still around, sort of. The dregs of Tokyo’s previous residents are split into two groups: souls and Manikins.

Souls came from the people who died in the Conception. They appear as glowing motes, transparent suggestions of their former bodies in various inhuman hues.

For the most part, they remember their lives, and they embrace or resign themselves to continued existence in the Vortex World. They shop with the new currency, give directions, hook up with each other, get invested in the politics of creation. The Vortex World is so weird that talking with the dead hardly registers as strange, but they are one step removed from humanity.

A disparate population of souls takes up residence in the Amala Network, seeking solitude after having felt the alienation of the Vortex World for themselves (though some are clinging to their feelings from the previous world). Eventually, they rally behind Isamu’s Reason of Musubi, which aims to create a world where everyone lives in isolation.

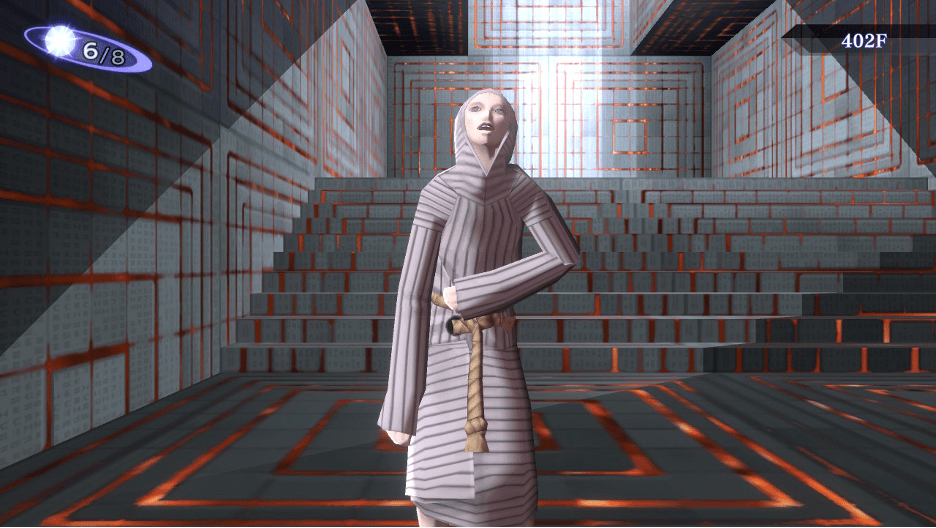

The initial search for Isamu and Yuko takes the Demi-fiend into the Great Underpass of Ginza, a cavernous waterway with mazelike utility tunnels. Inside, he encounters a group of strangers in identical hooded robes. Manikins, who, it turns out, aren’t human at all.

An old Manikin asks the Demi-fiend, “Are we so peculiar to you?” The very first soul the Demi-fiend talks to asks him the same question, but with Manikins, it can be tempting to say ‘yes’.

Manikins rarely make eye contact with the Demi-fiend when talking to him, preferring to look overhead like sunflowers toward Kagutsuchi, even when cut off from the sky. Some have unnerving expressions, weird haircuts. They have no eyebrows, a classic way to make a character seem off without the audience being able to immediately pinpoint why. Some mutter to themselves, and most have a frequent upper-body spasm that affects them at the same time. The motion makes it a little unclear what’s under their skin.

In other words, they’re full-time residents of the uncanny valley.

Manikins don’t think of themselves as another iteration of humanity. They’re not demons, either—if the Demi-fiend attempts to negotiate with one, they’ll misunderstand, thinking he’s asking if they want to be friends. They are the remnants of humanity’s strong emotions, which combined with mud into sentient, if sometimes unnerving, life.

Nocturne isn’t shy about using casual body horror. Their uncomfortable likeness to humans interrogates the biases and barriers that make humans view other humans as more ‘other’ than ‘human.’ (It’s not for nothing that Manikins have a wider range of body sizes and ages than the human cast, and several are implied to be queer).

Individual Manikins aren’t one-note manifestations of any given emotion or unfulfilled desire. Each Manikin is thoughtful, or reactionary, or easily frightened, or diligent, selfless, a little deranged, depending on what’s happening—as is anyone.

In each of them is the intermingling of the emotions that drove humanity to its best and worst. Necessary microcosms to keep in mind, when the Demi-fiend’s friends seem to be in a competition to show what horrors humans are capable of, in the name of some greater purpose.

Even more so than souls, Manikins serve as a reminder that other humans are not like you, and the success of bridging that gap depends somewhat on accepting the idiosyncrasies of others—and being aware of your strangeness to them.

Souls and demons have countless motivations spread among various alliances. Most Manikins, though, share a common motivation—to escape their persecution and enslavement.

Manikins, like humans and souls, are sources of Magatsuhi. And like most humans and souls, most Manikins are weak, unable for the most part to make use of their own Magatsuhi to defend themselves. Because of this, the existence of Manikins makes other humans reject unidealized aspects of humanity. A crucial aspect of Chiaki’s eventual persecution of the Manikins is her need to reject her own weakness. It’s no coincidence that it happens after she absorbs the demonic power of Gozu-Tennoh, the leader of the Mantra, the Manikins’ oppressors. For all the Vortex World’s strangeness, their oppression is very familiar to the injustices of the previous world, even if that oppression is being carried out by the comically demonic and being inflicted upon the uncanny.

ELEMENTS OF ALIENATION WORKING TOGETHER: KABUKICHO PRISON

After Isamu is freed from Mantra HQ, he tells the Demi-fiend he’s heard about a Manikin prophet held at the prison. Isamu is desperate for any help finding their teacher. He figures he can’t be in any worse danger there than he is now, and—for some reason!—sets off by himself. The Demi-fiend follows.

The Conception must have liked Kabukicho, but not that much, because only one building survived. The surrounding desert is dangerous, flooded by a Superfund site’s worth of Magatsuhi in an agitated, life-sapping, environmental form. Considering that the Mantra just heap decomposing Manikin bodies in fountains, this is probably a kind of run-off from the facility.

In the previous world, Kabukicho Prison, or at least the top floor, seems to have been a hostess club called The Medousa. Cute, considering it’s under the control of an ex-Mantra snake demon called Mizuchi. (This would not be the series’ only play on the ‘sex dungeon.’ In Strange Journey, the demon Mithras runs excruciating experiments on captured humans in red light district-inspired Sector Boötes, while Persona 5 ‘s first section involves a high school coach’s subconscious vision of the student athletes as slaves in a medieval castle.)

When the Demi-fiend gets to Kabukicho, there’s no sign of the Mantra, their Manikin prisoners, or Isamu. The quiet building is in disarray, but it’s hard to tell what’s the Conception’s fault. Mantra demons might have smashed the lights, torn down the flyers and shoved the furniture around at some point, but they probably didn’t pack up those moving boxes with neat lines of tape. If not for the eerie, sourceless purple and green light cutting swathes across the floor, this could just be a failed business in the previous world.

The soul near the door insists otherwise. “This is just a run-down building? You got it all wrong, pal. Clearly, this is a prison! Even though the Mantra fell, there’s still loads of Manikins being held here.”

The Manikins are a familiar but strange people, imprisoned in the familiar but strange environment. In a small room nearby, empty except for a near-barren bar and some kicked-over chairs, the Demi-fiend hears a voice: “Save us… We’re trapped in the mirage…”

Around the corner, at last, is evidence of the Mantra. A strange swirling light framed with glowing gold stone has been brute-forced onto the wall, cracking under the pins, attended by an “ex-guard” Naga.

The Naga disappears into the portal, and soon it can be heard taunting a screaming Manikin with comical sadism. The Naga returns and recognizes the Demi-fiend by reputation, but insists that the time of the Mantra’s relevance has come and gone: “Whatever you did during that attack on Nihilo doesn’t mean shit here!”

The small world of the Mantra has lost its power, but the Naga is of that world, not the Demi-fiend. From the defeated Naga, the Demi-fiend takes the Umugi Stone, the key to stepping into the mirage.

Kabukicho Prison used to be a club, but the music has little to do with that, or Mantra HQ’s complex, building, ominous theme. Mantra HQ’s jail juxtaposed a stripped-down version of the upper levels’ theme with a melancholic melody in strings-like synth. The music here is a closer relative to the Great Underpass of Ginza, with the repeating ebb and flow of a stoney, reverberating tone over shifting sounds. The effect is not so much ominous as it is displacing.

As soon as the Demi-fiend enters the mirage, the reverberating tone is sped up and reversed, grounded by percussion and a melodic progression, if not a melody. The result is oddly calming, relying on its juxtaposition with the brutal imagery of the bound and bleeding Manikins for dissonance between the senses.

In the mirage, the Demi-fiend stands on the ceiling, an unmissable cue to consider the familiar from a new perspective. The air around him wavers exactly like a mirage in the desert under the sun, evoking the Vortex World even inside. The building is flipped and desaturated, but things from the Vortex World are immune to the gray: the Demi-fiend, the Mantra’s shining gold prison bars and torture devices, and the Manikins themselves, a more solid and complex gray, lit with the soft red glow of their own bleeding Magatsuhi. Spilled blood and mud are streaked all over the floor, only visible in the mirage.

Together with the changed music, it’s as if to say, the mirage is where everything important is happening. The mirage not an illusion; the world is upside down and the comfort of the ‘right’ side will only hold you back.

Due to the obstructions and collapses in the building, the Demi-fiend has trouble fully searching the building. The mirage seems to affect beings differently, depending on whether they’re demons, souls, or Manikins. This inconsistency is a reminder of the imbalances in how the new world treats its inhabitants. He surprises a Manikin attempting to dig their way out, who breaks their spoon and demands that the Demi-fiend “take responsibility” and get a new one from the Collector Manikin.

Most Manikins are helpful enough to just tell the Demi-fiend where they think the Collector Manikin is, if they know. One, however, says “Gosh, I’m just to [sic] BROKE to remember! Maybe 100 Macca will REFRESH my memory! Hint hint!”

Whether this Manikin comes off as amusing, annoying, or sympathetic, they’re imprisoned while the Demi-fiend is free. They’re in the same position as all the other Manikins, but in this moment, they have something the Demi-fiend needs. Unlike the other Manikins, this one bargains for the immediate thing the Demi-fiend can probably hand over—Macca—rather than what he possibly can’t—freedom.

Once the Demi-fiend climbs enough emergency ladders the wrong way, strategically steps in and out of the mirage, and falls through the right holes in the ‘floor’, he finds the Collector Manikin. Between tortured coughs, the Collector remembers the Demi-fiend as the demon who found him a 1000 yen bill in exchange for help getting through the Underpass.

The Collector makes a lot of unhappy noises that suggest he would be far less willing to hand over his prized spoon if not for this previous exchange. He then adds, “While you’re at it, um… Would you maybe mind rescuing me?” in a voice that’s equally plaintive and passive-aggressive.

The digging Manikin takes the spoon without thanks. Others beg the Demi-fiend to save their prophet, not themselves. One has even kept track of where Isamu is.

The spectrum of selfishness and selflessness is on display in this harrowing place. In having to wrangle with each Manikin as an individual, the Demi-fiend must deliberately choose how he regards them as a group. Either he helps them all escape, or none of them, and he can’t help Isamu without also helping all Manikins.

Then there’s this repeated plea to save this other guy, who’s sort of the reason Isamu’s gotten himself trapped here in the first place. Maybe the Demi-fiend believes in Isamu’s plan, in which case, freeing the Manikins’ prophet becomes a little selfish. For whatever reason, he defeats the water snake Mizuchi and the mirage is dispersed. He then learns someone in this prison was clinging to life, knowing with sureness in his heart that the Demi-fiend would save him. It just wasn’t his friend.

Futomimi is the first to emerge. He prophesied this rescue, but that doesn’t stop him from thanking the Demi-fiend for doing it. He soon diverts the Demi-fiend’s attention to the other room, sharing his concern about Isamu’s ‘strange energy.’ After more thanks and more concern, this time for the other Manikins, he politely excuses himself.

This overabundance of social grace is unexpected, and only becomes more jarring after what follows.

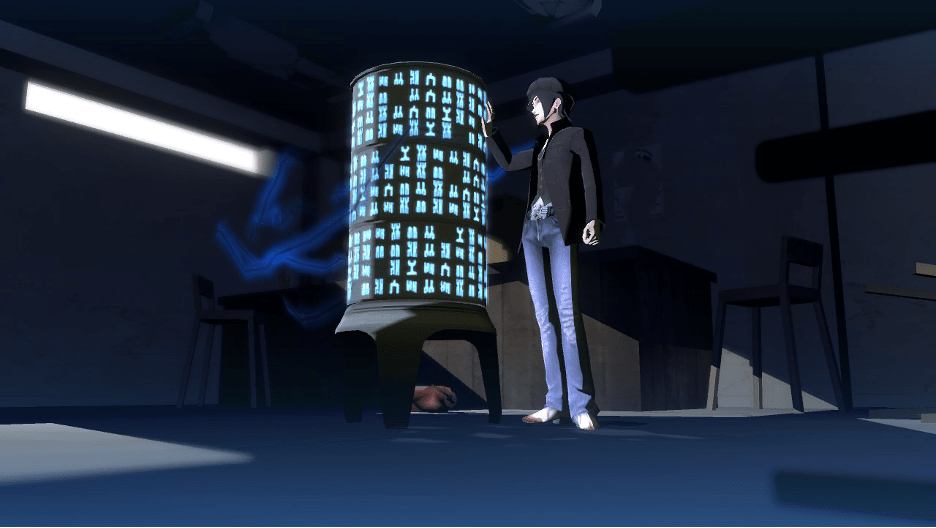

In the other room, Isamu doesn’t even notice he can leave until the Demi-fiend interrupts him. He’s been locked up with an Amala terminal, and can barely tear himself away.

The last time they’d spoken, Isamu was full of what-do-I-have-to-lose bravado. Now, he tears into the Demi-fiend, saying he can’t count on anyone but himself before announcing he’s going to pursue his own truth inside the Network.

Isamu’s and Futomimi’s voice actors, respectively Robbie Daymond and Hugo Pierre Martin, give richly layered performances under Christian La Monte’s direction (as they do throughout).

Isamu’s voice is sandpaper rough with bitterness, growing more forceful with anger before softening to brittle despair. It pitches high as he shares his revelations about truth and self-reliance. A hollow parody of the bravado heard in earlier conversations takes over as he accesses the Network, but his voice becomes so small the moment before he disappears.

How long has Isamu been in there? It seems like he’d only gotten the equivalent of a half hour’s head start, tops. Yet he had enough time for his will to be broken by torture, and for him to decipher an Amala drum and find his way into the Network just as Hikawa did.

Here again is that strange unevenness of time. It ultimately doesn’t matter how long Isamu was there because what’s important is what he experienced in that interval, and how it made him feel. Either the Demi-fiend finds Isamu’s breakdown understandable, or he doesn’t, but it doesn’t calm Isamu down.

After Isamu conducts his own escape via the Network, Futomimi seeks out the Demi-fiend again, having apparently found his own gratitude an insufficient trade for the Manikins’ lives. He offers his own gift, prophesying the Demi-fiend’s next steps.

Futomimi’s unexpectedly deep voice, oddly resonant for the assumed acoustics of the room, is filled with gratitude and concern, which grounds the weirdness of his mystical confidences. For all his composure, his words are peppered with upticks of relief and wavering breaks. This reveals a man compelling himself to set aside his own pain and get it together for the sake of the others, who nevertheless makes it a priority to treat the Demi-fiend with respect.

His graciousness can be a balm after Isamu’s anger. It can also be a source of discomfort, because it comes from someone who isn’t Isamu, because it comes from a Manikin, because it comes from a stranger whose mystical side invites skepticism, or just because it feels like too much. Even if the Demi-fiend doesn’t expect gratitude from Isamu, Futomimi still offers it while Isamu doesn’t. No matter what, it can be tough to stand there through Futomimi’s thanks and not feel worse about the fight with Isamu.

Isamu is caving to the pressures of the Vortex World. He’s carried over his expectations of the people he knew from the world that came before, and he’s struggling to understand how they fit into this one.

Friends get to be terrible to each other in a way that strangers don’t. Isamu has proven himself to be the friend who needs his terrible moments excused when he’s stressed. But what comes up in that kind of relationship is the question, over and over again, of how much can anyone manage.

Under the Network’s influence or not, Isamu has asked himself that same question, about the Demi-fiend, and everyone else, and he’s made his decision. Screw everyone.

Isamu is done with their friendship, and cuts one of the few ties the Demi-fiend has left to his humanity. Right after, the inhuman reaches out with what might have formerly been called human decency.

Where does the Demi-fiend belong? Does he need to belong anywhere?

The Vortex World doesn’t stop for this question. Futomimi leaves with the other Manikins to try to live together in peace in Asakusa, and Isamu will soon emerge as a sort of hermit thought leader in the Amala Network, considering this same question of isolation. Kabukicho Prison, too, changes.

If the Demi-fiend goes back, he’ll find that two groups are fighting over the collapsing building: a bunch of souls and demons, and the so-called ‘Emperor’, who is responsible for the freezing temperature inside. The sourceless purple and green light is diffused by the chill, making the former prison an ethereal dream. While the mirage no longer works, the frame and its inner light are still aglow, more abandoned junk from another era, along with the moving boxes and the scattered furniture. The souls and a remaining Naga could be considered a part of this same accumulating detritus.

The souls have apparently made the building a hostess club again, as it was in the previous world. Makes sense, considering the success of the nightclub in Shibuya. Anyone foolish enough to get lured in by the (possibly weirdly nostalgic) promise of “the hottest babes in town” gets attacked by a group of weak, haglike Datsue-bas.

The Emperor is Hee-ho the Jack Frost, a minor demon turned into an oversized Black Frost (echoing Mizuchi) in his quest for power. He’s gathered together a group of Jack Frosts to inhabit his tiny empire, a coda to the Mantra, set to goofy music.

He tries to kill the Demi-fiend and melts. Another small world, gone, in the cycle of growth, stagnation, and decay that cannot stop, even in the womb of the new world to come. Presumably, the scammy souls take over until they bite off more than they can chew, and are scattered or devoured in turn.

ALIENATION AND THE REASON OF MUSUBI

Isamu is the Demi-fiend’s snarky-yet-amiable friend who dresses to impress, but only succeeds in revealing how much he wants others to think he’s got it all figured out. Kabukicho Prison is where Isamu’s Reason of Musubi is born. Or rather, it is the site of his own Conception—his break with his personal previous world and his departure into the new via the Amala Network.

While Hikawa’s and Chiaki’s Reasons are fixated on guiding the choices of the people who would inhabit their new worlds, Isamu’s Reason is primarily about insulating those inhabitants from each other’s choices.

“To be honest with you, I stopped caring about people entirely,” he tells the Demi-fiend inside the Network. “… The way I see it, there’s me, and there’s everyone else. Most people don’t even notice I exist. They don’t care about me, and I sure as hell don’t care about them. To me, that’s neither empty nor sad.”

The World of Musubi would be like the froth of waves upon the shore: bubbles and individual flecks of life, like sediment, separate but adhered into the shape of a greater whole. Everyone is reborn into their ‘own little world’, creation and destruction at their fingertips, and no one is beholden or vulnerable to anyone else. No acceptance, no rejection, no powerlessness or estrangement. In theory, isolation without alienation.

Some players would agree with Musubi if that speech showed up on the intro screen like the Scripture of Miroku, no context needed; some would never want to live in a world like that after playing the game for hundreds of hours. Regardless, all these elements of alienation throughout the game come together so that Isamu’s ideology makes sense. The player understands what happened to Isamu’s ideas of his relationship to others under the extreme conditions of the Vortex World.

Where the Demi-fiend crosses paths with the Reason of Musubi, these elements become impossible to overlook.

MUSUBI IN THE AMALA NETWORK

The Amala Network is the Vortex World infrastructure though which Magatsuhi flows. Initially, it’s the tool of Hikawa and the Assembly of Nihilo. Hikawa siphons from it to serve his Reason, and demons enter it to satisfy their own hunger. Some souls also go into the Network to seek solitude.

Inside, the music is back-of-the-neck tingly and nonmelodic. Even though the Amala Network is the way that the Demi-fiend travels from one region of the Vortex World to the next, it is very difficult for him to find his way if fast-travel is disrupted. The passages are composed of identical golden walls and black voids, with Magatsuhi flowing underfoot and overhead.

The layout shifts, and if there’s any logic to that layout in the first place, it’s the logic of Kagutsuchi, that great Tetrisphere in the sky. To get the Demi-fiend through, the player has to rely on a progress-contingent map and rote memory, and hope that the connections between areas don’t get blocked off or shuffled around as soon as he turns his back.

If they do, then the Demi-fiend is trapped, utterly reliant on either Hijiri’s skill with altering the flow of the Network to move forward. (How many souls ducked in to see if this solitude was a good fit, only to find they couldn’t escape, and eventually, no longer wanted to?)

These souls occupy dangerous infrastructure. This is different from the souls who make do in the ruins of Shinjuku Medical Center, or even the Manikins who live in hiding in the Great Underpass of Ginza. This is a toxic pipeline.

A soul in the Network tells the Demi-fiend, “You see the red things running along the floor and ceiling? That’s all Magatsuhi. Magatsuhi is born from the flow of emotions, such as suffering, anxiety, sadness…”

The effect it has on people isn’t a secret; a gossipy soul at Nyx’s Bar in Ginza remarks that Isamu “probably became enchanted with Magatsuhi as he kept accessing those terminals.”

Magatsuhi appears in many forms in the Vortex World. Some forms of Magatsuhi flood the minds of humans with negative emotions, and it’s possible that it erodes the minds of souls.

In Shibuya, the Demi-fiend runs into a soul outside the nightclub who picks a fight. That fight ends up being a formal battle against a Will O’ Wisp, a Foul demon that is little more than a dark purple mist with kabuki mask-like outlines of a grimacing face. (For those tracking the antisocial empty face motif, Sakahagi’s demon form is also categorized as a Foul).

After the fight, the aggressive soul cowers and offers information, but few Fouls outside the Network are so easily understood. Fouls are particularly tricky to negotiate with; they speak in ghastly moans. The Demi-fiend can sometimes get them to join him when Kagutsuchi is shining bright, but it kind of feels like taking advantage of a drunk.

It’s not clear if all souls are also Fouls, or if there is a point at which a soul becomes a Foul, if they lose the capacity to understand or think in a human tongue, or, for those furthest gone, if they have desires beyond Magatsuhi. The longer they spend in the Network, the bigger the gap between themselves and their former human lives.

Every time the Demi-fiend visits the Amala Network, its souls are less approachable. At first, it seems like for every soul that tells him to get lost, there’s a soul helpfully pointing out some danger of the network. Even those grumpy souls help the Demi-fiend go away, healing him or pointing out a place where he can communicate with the outside world.

The second time he enters the Network, seeking Isamu, the grumpy souls double down—but then again, the Demi-fiend has already talked to some of them, and knows they want to be left alone. This may be a result of the time that these souls are spending in the Network, or that he is in a different location where less friendly souls have chosen to gather—safety in isolation in numbers.

He runs into a scattered group of fouls. They seem to want to be alone for different reasons. One is philosophical: “To be strong is to be solitary. There is no such thing as ‘loneliness.’” Another is begrudging, telling themselves more than the Demi-fiend, “Society didn’t shun me—I shunned society!” A third is cantankerous, growling “I do whatever I damn well please. Nobody can tell me what to do.”

These Fouls close off the corridors if he gets too close, shunting the Demi-fiend off into warp voids. There is no recognition of the Demi-fiend in these exchanges. This isn’t a conversation. They’re just saying what’s going on in their heads, a parody of the scenes in which his friends or Hikawa push the boundaries of conversational decency and reciprocity to monologue about their ideologies. This is communication breakdown, once-human beings making no meaningful contact.

Not all Musubi’s followers are antisocial on principle. A foul engages in an elliptic but considerate exchange about solitude before it invites the Demi-fiend to talk to Isamu. It says that we all live on our own, whether we think we do or not, and adds, “You are me.”

Since this is a Shadow foul, it’s a guess whether this parting remark is just a shout-out to spin-off series Persona’s Jungian encounters with shadow selves. If the Demi-fiend chooses to support Isamu’s ideology, it highlights the necessity of the two recognizing each other in a common cause, even as Isamu decides there’s no bridge left to burn.

For such amiable souls, the gulf between the Demi-fiend and themselves is that they have their own reasons for wanting Musubi brought into being, and it’s counter to Musubi’s ideals to care if anyone else knows what those reasons might be.

MUSUBI IN THE AMALA TEMPLE

The Reason of Musubi gains its god at the forgotten Amala Temple. The music, peaceful ambience on the surface, gains depth with pushing, percussive strings and discordant chord progressions. It evokes the feeling of visiting an old and beautiful place of worship for an unfamiliar faith.

According to one rude old soul, the Amala Temple “enshrines no god, nor does it have worshipers who pray. Nonetheless, all the Magatsuhi in the world originates here.”

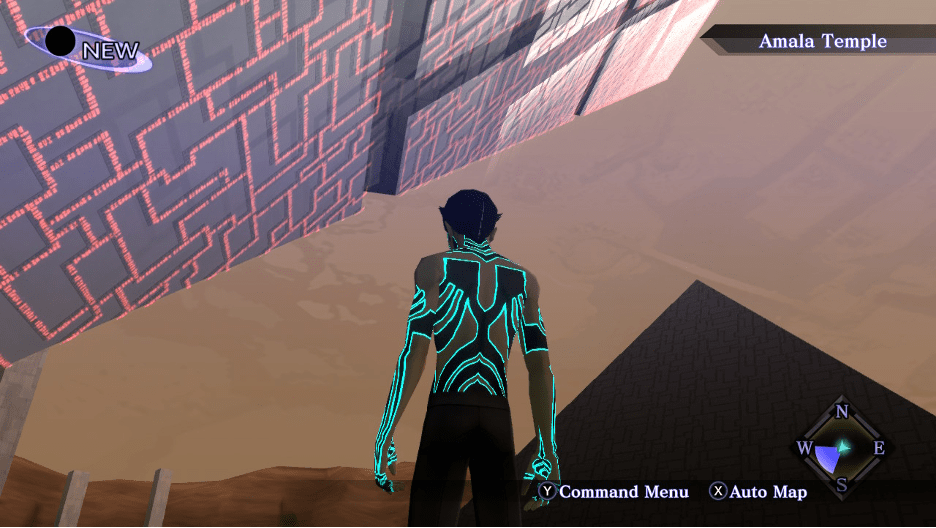

The temple sits in an elevated (un)natural basin, three pyramids built over a reservoir of Magatsuhi with a fourth floating in the center. Their exteriors are Kagutsuchi architecture, glowing lines of emotional mortar and Amala glyphs between dark stone.

The interiors are a mystery. For a place that worships no gods, they are distinguished into Red, Black, and White Temples for some purpose. Inside are varying elements of traditional Japanese architecture, known and reinterpreted by someone with an artistic vision, at some point, now forgotten and gone. The pyramids are bigger on the inside than the outside, and the Demi-fiend has to navigate their warp puzzles, shadow realms cast by unknown light sources, and places of utter darkness.

It feels like intrusion, though that’s a small transgression in comparison to the ritual murder of Hijiri that follows. Neither actually are transgressions, though. This is what the world is for. Isamu is here to fulfill this mysterious place’s purpose. Three demons block the flow of Magatsuhi to the central temple, and Isamu can’t move forward without the Demi-fiend’s help.

From the beginning, there’s been a clear imbalance in their friendship, even if the abandoned hospital is too unnerving to perfectly represent the dynamics of their relationship. It’s easy to get the impression that he’s regularly doing weird, big ask favors for Isamu, and committing himself to the work of whatever situation while Isamu benefits, even if it’s not for Isamu’s sake.

Friendships are not balance sheets. But it kind of feels like he mostly gets 2000s teen I’m-mean-to-you-because-we’re-friends snark in return. After Isamu’s emotional breakdown in Kabukicho Prison, it becomes clear that the harrowing Vortex World isn’t going to be the crucible from which Isamu emerges a better friend than ever.

It doesn’t help that the Demi-fiend’s new ally, Hijiri, falls prey to the maddening influence of the Amala Network just like Isamu, and probably tries to kill Isamu for control over the Network. He definitely puts together the method to ritually murder the Demi-fiend or Isamu at the Temple to gain enough power to guide the new world. As if Isamu needs another reason to want a world where nobody would interfere with his life.

(Hijiri is fixated on the hidden knowledge the Network provides, not its social aspects; who knows how Musubi’s antisocial ideologies would have manifested if this game had been made after the spread of social media).

The Demi-fiend can chase Hijiri and Isamu to the Amala Temple for any number of reasons. Maybe he’s worried about Hijiri, or Isamu, neither, both. Isamu doesn’t give him the chance to make his intentions clear.

“I seriously don’t know what prompted you to come this far,” Isamu says. “Whatever your deal, I’m done playing guessing games, with you and everyone else.”

Isamu treats their friendship like a cruel joke, or a knife wielded in self-defense. If the Demi-fiend says he’s here for Hijiri, then Isamu holds Hijiri hostage and makes the Demi-fiend clear out the three demons. Otherwise, Isamu says that the Demi-fiend is free to further Musubi’s cause.

No matter why the Demi-fiend helps Isamu, Isamu is just such a dick about it. He cracks snide jokes about sitting back while the Demi-fiend does all the work, makes backhanded remarks about the Demi-fiend’s strength, about them not really being on the same side. And he doesn’t even have the courage to say any of this to the Demi-fiend’s face.

Sure, Isamu’s probably feeling the friction between his ideology and his reality. He needs the person he believes has hurt him beyond forgiveness. For the Demi-fiend to do what Isamu wants, he has to ignore all this sniping. To support Musubi, though, the Demi-fiend needs to sit through all that sniping, and then listen to Isamu, take him at his word when he says that Hijiri was planning on killing either of them first.

Either that, or not care what the truth is anymore. What happened doesn’t matter, only making Musubi a reality. And then one more time, to really support Musubi, the Demi-fiend needs to do Isamu’s scary, dirty work for him: he needs to be the one to kill Hijiri to summon Musubi’s god.

By this time, antisocial behavior and murder can’t be that surprising of a pairing; it’s just surprising to face it coming from Isamu. Sakahagi, member of the empty face motif club, was ostracized from the Asakusa community because he preyed on other Manikins for their Magatsuhi. Sakahagi wanted power, like Isamu, to keep others from having power over him, but he didn’t dream of a new world founded on that desire.

There is a point at which the Demi-fiend can tell Isamu ’no’. It doesn’t save Hijiri, and it doesn’t keep Isamu from summoning the god that will bring Musubi into being.

Why was the Demi-fiend ever friends with this guy? The player doesn’t know anything about how they became friends, just that, despite Isamu’s faults, he liked Isamu’s company enough to choose to spend time with him when he doesn’t have to. But the previous world is gone, and Isamu is determined to make sure that his previous self is gone, too.

Any doubt about the Demi-fiend’s friendship with Isamu potentially proves Musubi’s point. Are other people worth the risk that they might one day prove to be entirely different from your conception of them?

SUFFICIENCE OUTSIDE ONESELF

The Vortex World runs on other people. It’s connected by rumor and gossip, and it’s powered by the strong emotions and experiences of the people who died in the previous world—and die again in this one. If the Demi-fiend feels as isolated as the player does, it’s not because of the ruins around him, but the strangers who inhabit them. Gradually, though, some of these strangers recognize him, remember what they talked about before, and pick up that conversation again. There is continuity amid the chaos.

The demons, souls, and Manikins that inhabit the Vortex World are people, and their difference from humanity is an artistic exaggeration of the gulf between any two humans. And sure, other people are guessing games, but it’s sometimes worth making the deliberate choice to keep playing—even when the big heady future of the world isn’t at stake.

There’s common cause to be sought in others, whether that’s material help, companionship, or larger change. Even Isamu knows that he can’t gather the necessary support for the Reason of Musubi unless he envisions a world in which everyone, not just himself, gets a world of their own.

There comes a point at which even the Vortex World’s dizzying sky becomes familiar. The shapes of the old-new cities become more easily recognizable than constellations ever were, even if the Demi-fiend doesn’t quite have a home in any of them. What would it be like to look up at night and see the glimmer of a city on another continent instead of a constellation hundreds of lightyears away? Would that remind you of how much you have in common with them, or of their distance?

Leave a reply to SERIES MASTER POST: An Un-Wiki Intro to Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne – Mercy Calder Cancel reply